-

-

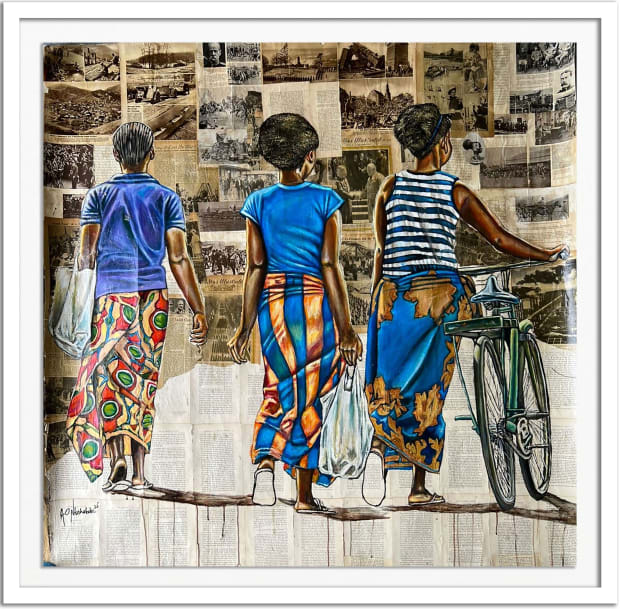

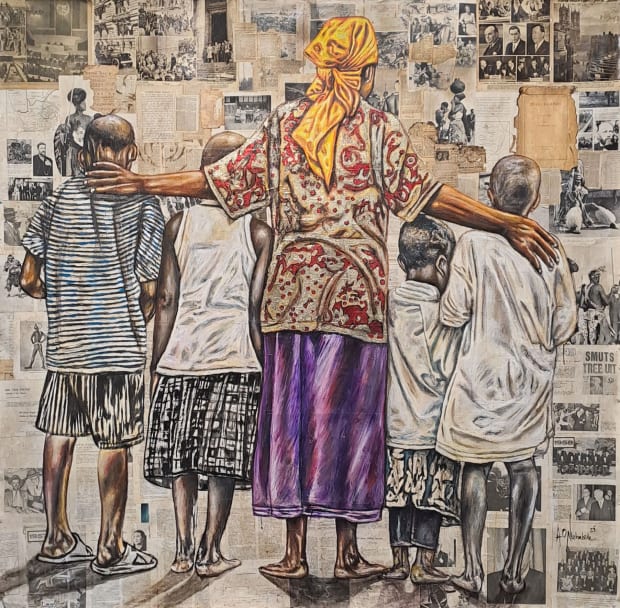

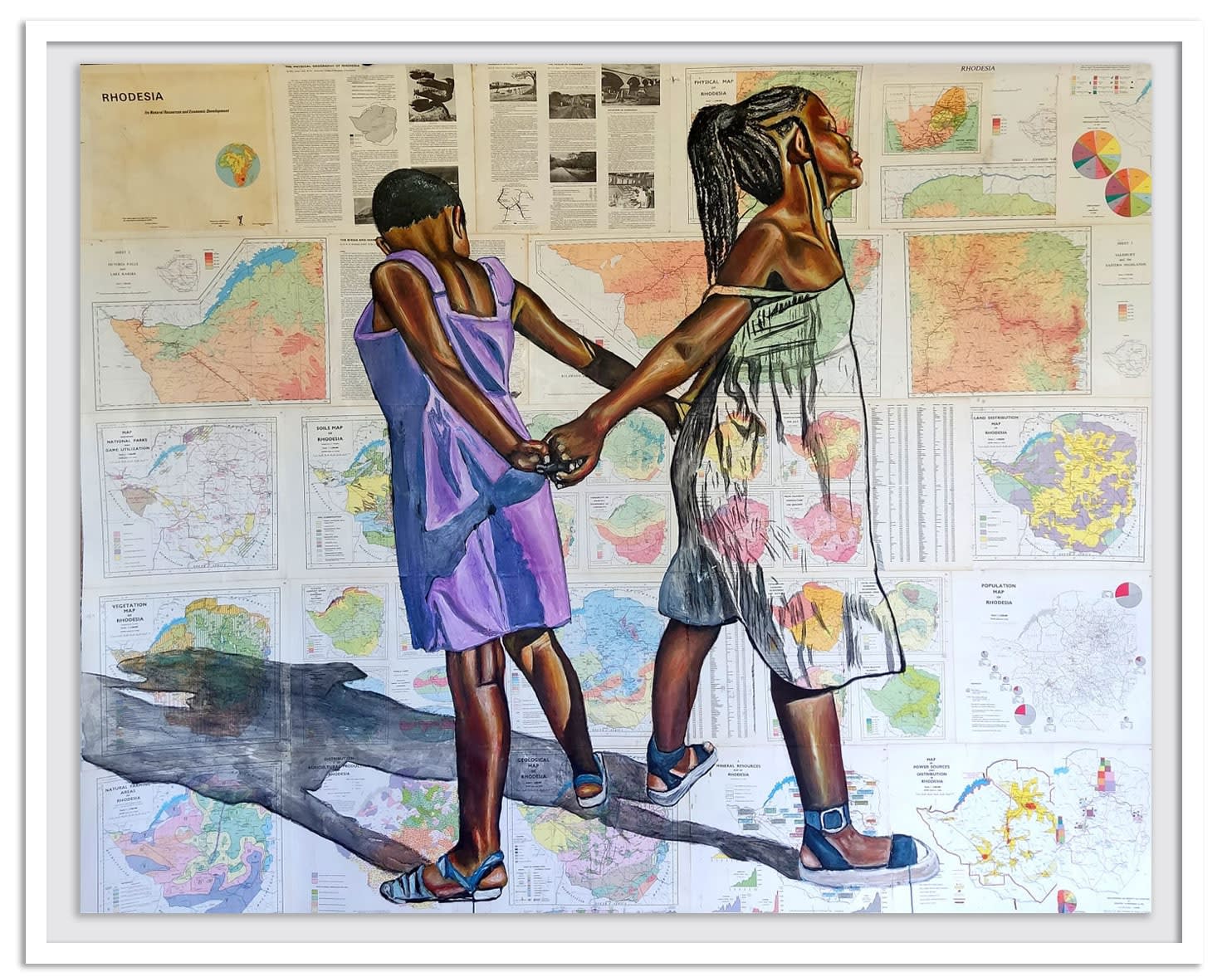

Q: Would you say that your work engages with current dialogues around artistic decolonization?A: When I see what other fellow Black artists are doing, there is a strong sense of pride. We want to show that we are painting ourselves now, not landscapes. We want to be seen, we want our children to be seen. What I am seeing now is that Black artists are painting Black figures. So I would say that my work does engage with artistic decolonisation. At the same time I do not want to cause division, but I want to show the reality, that in the background, this is what happened. I want people to know that we come from a past of pain, that we continue to carry the pain and we do not want our descendents to carry that same pain, but still we do not want them to forget. We want them to know, so that they are stronger, and that going forward, they know that we come from this, this is how we have risen up.

-

-

Q: In some of your artworks the historical artefacts are burnt. Would you say this process of burning that you incorporate possibly hints at notions of burying or rebirth for the country and for the continent?A: I started burning certain elements in some of my artworks during a period when I felt I needed to let loose and stop playing safe. The burning occurs toward the end of creating my artworks. I initially wanted to create an effect of tearing away. The images and the angles of the artworks hint at rebirth for myself and subconsciously a wish to burn away the pain of the past. I was thinking what if colonisation never happened, how would Africa have developed. The act of burning is both physical and spiritual.

-

-

Q: Your subject matter is informed by your environment. Please elaborate on this.A: I am originally from a rural area and I moved into a suburban area with my mother who worked as a domestic helper. It was a cultural shock moving from a rural area into an urban area, because I had to adapt to different cultures and different racial groups. I moved to the inner city of Johannesburg during the early 90s just before apartheid ended. This was another culture shock for me moving from a suburban area into a city space that is polluted and densely populated. This was something I had not experienced before and I think this is where my artwork shifted, because I wanted to reflect on my surroundings; what I was seeing for the first time.When I was at university my earlier works were based on people living in the inner city, particularly the homeless and informal waste collectors. But I would not paint them as they were, I would paint them with vibrant colours to signify that despite their circumstances they are not without hope and dignity. During this time I also depicted pollution - how it moves through the environment from Asia and First World countries, inevitably ending up dispersed throughout Second and Third World countries in the Global South, only to become trash that is sold cheaply.

Q: You photograph scenes of daily life and then translate that onto canvas. Why the choice to depict the outer world rather than that which is internal, as in your own inner world?

A: The reason why I depict the outer world can be traced back to my time at university where I would walk and commute. I would carry a camera and whatever I found interesting, I would capture it and translate into an artwork. In a sense, I am photographing what affects in the present moment and at that time it was informal settlements and lifestyles of workers in the informal sector in the city. But I had to move away from it because painting those groups of people and scenery began to weigh heavy on me psychologically; depressing me to a certain extent. However, I did not want to go into commercial art, instead I wanted to strike a balance.

I get affected by where I stay, so my artwork is rooted in feeling - because I thought about the unfairness of inequality and I wanted to highlight that in my artwork. If it was not a feeling, I would not have been moved to paint it. There was an inward compassion toward injustice and that is where the link to history filtered into my art. So I would say that the outer world influences my inner world.

Q: In a statement you said that you have lived in the inner city where you have encountered poverty, pollution and urban decay. From this you have examined the negative impact of rapid urbanisation. Can you please expand on this.A: Like I said in the beginning when I moved to the city I encountered urban decay. Rapid urbanisation came with overpopulation, poverty, pollution and crime. There is also a lack of municipal service delivery. I understand that people migrate to the city in search of work and more opportunities, but with that comes a negative impact that is mainly on the infrastructure and the health of people living in cities, because a lot of city conditions are not desirable. -

Q: Your artistic inclination is influenced by your daughter, so your work has some references to childhood and all that it encompasses such as having a sense of joy, innocence, and wonder. Would you perhaps then say that your childhood has an influence on your work, possibly even unconsciously?A: As I mentioned previously I wanted to strike a balance, so I thought that I should paint something that could uplift my mood and my spirit. This is where my daughter factors in and when I started painting kids. My intention was to paint the kids in such a way that captures what they are thinking about, as well as what type of person I would prefer my daughter to be, because I do not want her to forget the history of our people and of our country.Yes I believe my childhood does have an influence on my work because I was there witnessing apartheid and the transition to democracy, to a post-apartheid South Africa. Those thoughts and experiences linger when you witness social ills and socio-political imbalances. I spotlight the children and mother, because I find that the father tends to be absent to meet the emotional needs of the household and so I think that my selection of mother and child images is often done unconsciously, but also somewhat consciously.

-

-

Aside from the historical artefacts, your artworks also include musical scores and poetry. I have two questions in relation to this.

-

Q: Firstly, what do these other artistic mediums represent for you?

A: I think music is therapeutic, especially because I did not have an easy childhood. So I just immersed myself into music, hence I use music notes in my work. At times, I also want the work to be playful, not too serious, because at times people have said that my work was too tense and serious. So I wanted to loosen up by using musical scores in particular.-

Q: Secondly would you say incorporating music and poetry into the background is to add an aspect of gentleness to the seriousness needed to contemplate historical artefacts that represent oppression and injustice?

A: The music and poetry is meant to soften the harsh realities of the historical documents. In Africa music is therapy and as Africans we quite often use music to heal. -